Turtles

Click on a picture below to jump directly to that Turtles information

Loggerhead Turtle (in St. Ives Bay)

This morning while on my NCI watch I was scanning the sea for any storm debris that may have washed off a ship such as timber or a large container, when a group of migrant Lesser Black backed Gulls hovered over something in the water, a careful observation saw a small head with a reddish/brown carapace of a very rare Loggerhead Turtle. I put the large Russian binoculars that came off the Berlin Wall onto the animal and watched it for some time making its way into the St. Ives Bay at a steady pace until I lost it when the Ocean Osprey sailed past the station. I continued to look for it but sadly could not locate it. The Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta), is a species of oceanic turtle distributed throughout the world. It is a marine reptile, belonging This morning while on my NCI watch I was scanning the sea for any storm debris that may have washed off a ship such as timber or a large container, when a group of migrant Lesser Black-backed Gulls hovered over something in the water, a careful observation saw a small head with a reddish/brown carapace of a very rare Loggerhead Turtle. I put the large Russian binoculars that came off the Berlin Wall onto the animal and watched it for some time making its way into the St. Ives Bay at a steady pace until I lost it when the Ocean Osprey sailed past the station, i continued to look for it but sadly could not locate it.

The Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta), is a species of oceanic turtle distributed throughout the world. It is a marine reptile, belonging to the family Cheloniidae. The average loggerhead measures around 90 cm (35 in) in carapace length when fully grown. The adult loggerhead sea turtle weighs approximately 135 kg (298 lb), with the largest specimens weighing in at more than 450 kg (1,000 lb). The skin ranges from yellow to brown in colour, and the shell is typically reddish brown. No external differences in sex are seen until the turtle becomes an adult, the most obvious difference being the adult males have thicker tails and shorter plastrons (lower shells) than the females.

This turtle is found in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, as well as the Mediterranean Sea. It spends most of its life in saltwater and estuarine habitats, with females briefly coming ashore to lay eggs. The loggerhead sea turtle has a low reproductive rate; females lay an average of four egg clutches and then become quiescent, producing no eggs for two to three years. The loggerhead reaches sexual maturity within 17–33 years and has a lifespan of 47–67 years.

The turtle is omnivorous, feeding mainly on bottom-dwelling invertebrates. Its large and powerful jaws serve as an effective tool for dismantling its prey. Young loggerheads are exploited by numerous predators; the eggs are especially vulnerable to terrestrial organisms. Once the turtles reach adulthood, their formidable size limits predation to large marine animals, such as sharks.

The loggerhead sea turtle is considered a vulnerable species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. In total, 9 distinct population segments are under the protection of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, with 4 population segments classified as “threatened” and 5 classified as “endangered” Commercial trade of loggerheads or derived products is prohibited by CITES Appendix I. Untended fishing gear is responsible for many loggerhead deaths, and Ocean plastics. The greatest threat is loss of nesting habitat due to coastal development, predation of nests, and human disturbances (such as coastal lighting and housing developments) that cause disorientations during the emergence of hatchlings. Turtles may also suffocate if they are trapped in fishing trawls. Turtle excluder devices have been implemented in efforts to reduce mortality by providing an escape route for the turtles. Loss of suitable nesting beaches and the introduction of exotic predators have also taken a toll on loggerhead populations. Efforts to restore their numbers will require international cooperation, since the turtles roam vast areas of ocean and critical nesting beaches are scattered across several countries.

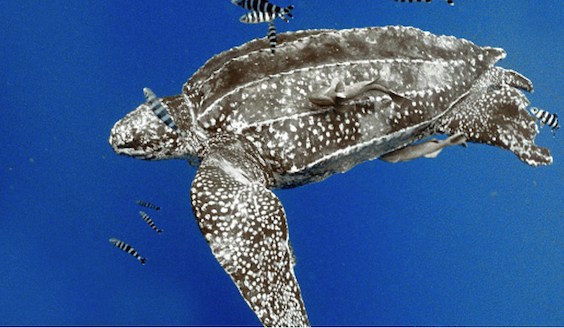

Leatherback Turtles

This very large species of turtle have been observed annually off the Cornish coast particularly off the Isles of Scilly. Leatherback turtles have the most hydrodynamic body of, all large, sea turtle’s with a teardrop-shaped body. A large pair of front flippers powers the turtles through the water. Like other sea turtles, the leatherback has flattened forelimbs adapted for swimming in the open ocean. Claws are absent from both pairs of flippers. The leatherback’s flippers are the largest in proportion to its body among extant sea turtles. Leatherback’s front flippers can grow up to 2.7 m (8.9 ft) in large specimens, the largest flippers (even in comparison to its body) of any sea turtle. The leatherback has several characteristics that distinguish it from other sea turtles. Its most notable feature is the lack of a bony carapace. Instead of scutes, it has thick, leathery skin with embedded minuscule osteoderms. Seven distinct ridges rise from the carapace, crossing from the cranial to caudal margin of the turtle’s back. Leatherbacks are unique among reptiles in that their scales lack β-keratin. The entire turtle’s dorsal surface is coloured dark grey to black, with a scattering of white blotches and spots. Demonstrating countershading, the turtle’s underside is lightly coloured. Instead of teeth, the leatherback turtle has points on the tomium of its upper lip, with backwards spines in its throat (esophagus) to help it swallow food and to stop its prey from escaping once caught. The largest verified specimen ever found was discovered on the Pakistani beach of Sandspit and measured 213 cm (6.99 ft) in CCL and 650 kg (1,433 lb) in weight.

The carapace of the leatherback sea turtle has a unique design which enables the sea turtles to withstand high hydrostatic pressures as they dive to depths of 1200m. Unlike other sea turtles, the leatherback sea turtle has a soft, leathery skin which covers the osteoderms rather than a hard keratinous shell. The osteoderms are made up of bone-like hydroxyapatite/collagen tissue and have jagged edges, referred to as teeth. These osteoderms are connected by a configuration of interpenetrating extremities called sutures that provide flexibility to the carapace, enabling in plane and out of plane movement between osteoderms. This is important since the lungs, and thus the carapace, expand when taking in air and contract when deep diving. Leatherbacks have been viewed as unique among extant non-avian reptiles for their ability to maintain high body temperatures using metabolically generated heat, or endothermy Leatherback turtles are one of the deepest-diving marine animals. Individuals have been recorded diving to depths as great as 1,280 m (4,200 ft). Typical dive durations are between 3 and 8 minutes, with dives of 30–70 minutes occurring infrequently.

Atlantic Subpopulation

The leatherback turtle population in the Atlantic Ocean ranges across the entire region. They range as far north as the North Sea and to the Cape of Good Hope in the south. Unlike other sea turtles, leatherback feeding areas are in colder waters, where an abundance of their jellyfish prey is found, which broadens their range. However, only a few beaches on both sides of the Atlantic provide nesting sites. Off the Atlantic coast of Canada, leatherback turtles feed in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence near Quebec and as far north as Newfoundland and Labrador. The most significant Atlantic nesting sites are in Suriname, Guyana, French Guiana in South America, Antigua and Barbuda, and Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean, and Gabon in Central Africa. The beaches of Mayumba National Park in Mayumba, Gabon, host the largest nesting population on the African continent and possibly worldwide, with nearly 30,000 turtles visiting its beaches each year between October and April. Off the north-eastern coast of the South American continent, a few select beaches between French Guiana and Suriname are primary nesting sites of several species of sea turtles, the majority being leatherbacks. A few hundred nest annually on the eastern coast of Florida. In Costa Rica, the beaches of Gandoca and Parismina provide nesting grounds. Leatherback sea turtles can be found primarily in the open ocean. Scientists tracked a leatherback turtle that swam from Jen Womom beach of Tambrauw Regency in West Papua of Indonesia to the U.S. in a 20,000 km (12,000 miles) foraging journey over a period of 647 days. Leatherbacks follow their jellyfish prey throughout the day, resulting in turtles “preferring” deeper water in the daytime, and shallower water at night (when the jellyfish rise up the water column). Mating takes place at sea. Males never leave the water once they enter it, unlike females, which nest on land. After encountering a female (which possibly exudes a pheromone to signal her reproductive status), the male uses head movements, nuzzling, biting, or flipper movements to determine her receptiveness. Males can mate every year but the females mate every two to three years. Fertilization is internal, and multiple males usually mate with a single female. This polyandry does not provide the offspring with any special advantages. Female leatherbacks are known to nest up to 10 times in a single nesting season giving them the shortest inter nesting interval of all sea turtles. The eggs hatch in about 60 to 70 days. As with other reptiles, the nest’s ambient temperature determines the sex of the hatchings. After nightfall, the hatchings dig to the surface and walk to the sea. The morphology of offspring has been found to vary with nest incubation temperatures. Higher temperatures resulted in lower mass, smaller appendages, narrower carapace widths, and shorter flipper lengths while lower temperatures resulted in greater mass, wider appendage widths, wider carapace widths, and longer flipper lengths.