Sharks

Click on a picture below to jump directly to that Sharks information

Basking Shark

The basking shark is the second-largest living shark and fish, after the whale shark, and one of three plankton-eating shark species, along with the whale shark and megamouth shark and is one of the Earth’s giants. Scientifically known as Cetorhinus maximus, the basking shark is the second-largest living shark, behind the whale shark. It is one of three passive sharks that eat plankton by filter feeding. The other two plankton feeders are whale sharks and megamouth sharks. Basking sharks used to travel the world’s oceans in great numbers, but those numbers have been declining steadily for decades and continue to drop. Despite their historical prevalence in the world’s oceans, modern scientists know very little about this gentle giant of the sea. An average adult basking shark weighs a whopping 10,200 pounds and grows to an average length of 26 feet. The largest ever recorded basking shark was caught in a fisherman’s net in the Bay of Fundy in Canada in 1851. It measured 40.3 feet. No one could weigh it at that time, but it’s guessed the basking shark weighed 45,800 pounds. Basking sharks are often mistaken for great white sharks. The most significant difference is the basking shark’s massive jaw, measuring more than 3 feet. They also have long gill slits that encircle their entire heads, which they use to feed with the help of hundreds of gill rakers. Typically, the basking shark is much longer and thinner than great whites and have smaller eyes. Basking shark tails have a distinctive crescent shape, and their skin is scaly with a layer of mucus over it.They are black, brown, or blue on top, and their colour fades to white on their bellies. They have a menacing appearance, which frightened many people throughout history However, basking sharks are among the most docile, passive, and harmless of the shark family.

Lifespan & Reproduction – Scientists know little about the basking shark. No one is sure how long they live, but experts say it’s probably about 50 years. When a female basking shark becomes pregnant, the shark pups inside her feed on other unfertilized eggs inside her womb, which is called oophagy. Oddly, the female’s right ovary is the only reproductive organ to function. No one knows precisely why. Females carry their pups from one to three years (the longest gestation period of any animal) and will give birth to several young. The pups are fully developed sharks when they are born and can reach lengths of up to five feet. However, scientists don’t have a firm number on the average litter size, although their best guess is around six.

Habitat – Where does the basking shark live?

Basking sharks follow concentrations of plankton. That means they live in most of the world’s oceans, including the Mediterranean Sea. Basking sharks like water between 46°F and 58°F, however people have seen them in warmer water. It’s thought basking sharks may migrate to and from temperate latitudes on both sides of the equator. Basking sharks are found close to shore and spend a lot of time on the continental shelf. They are often spotted on the surface feeding, although they can dive to around 3,000 feet. Basking sharks migrate with the seasons, following their food source.

Food & Diet – What does the basking shark eat? – Basking sharks love zooplankton. As a filter feeder, the species follows the dense populations of plankton near the surface. When they feed, they open their massive mouths and slowly glide through the clouds of plankton as the gill rakers remove the tiny plankton from the water. A basking shark can filter millions of pounds of water per hour. Unlike whale sharks and megamouth sharks, basking sharks cannot suck water through their gills to feed. They can only force plankton-rich water into their mouths by swimming.

Threats & Predators

Human Threats – Overfishing is the main threat to the survival of the basking shark. In the past, basking sharks were quite numerous and hunted for food, leather, and oil. They were easy prey because they feed at the surface and move very slowly. Overfishing in the last century decimated the basking shark population worldwide. For decades, Canada’s government tried to kill as many basking sharks as possible because they frustrated salmon fishing crews. Populations dropped by an estimated 90% on the Canadian Pacific coast. Fishing is still the most common threat, as people in countries such as China and Japan use its cartilage for medicine and use the fins for shark fin soup. They are often accidentally caught in fishing nets because they are so big and swim so close to the surface. It is illegal in some countries to keep living basking sharks caught in nets, and fishing crews must release them back into the ocean. I have seen Orcas kill Basking Sharks off West Cornwall.

Climate Change & Global Warming – Climate change and global warming will affect the basking shark in two ways. First, water temperature and salinity changes due to melting polar ice caps could be detrimental to the basking shark’s survival. The shark enjoys temperate water conditions, and warming sea temperatures will decrease the shark’s natural habitat. Second, because the sea absorbs much of the extra carbon dioxide in the air, the waters are getting more acidic, which isn’t suitable for many sea creatures such as coral or plankton. Changes in sea acidity could adversely affect zooplankton populations, which would lead to food shortages for these behemoth sea creatures.

Predators – Their enormous size means that besides humans, basking sharks have few predators. There have been instances where people have seen killer whales feeding on a basking shark’s carcass, and great white sharks sometimes eat dead basking shark bodies. Lampreys often attach themselves to basking sharks, but it’s doubtful they do any real harm besides leaving tell-tale scars on the sharks’ thick skin.

Other threats – Basking sharks feed on the surface and therefore are prone to get hit by boats. Basking shark pups are also vulnerable as food to other sharks

Conservation Status – Basking sharks were a common species about 100 years ago. They are passive and not afraid of boats or people, so they were easy targets for fishing vessels. People used the livers of basking sharks for oil, their skin for leather, and their flesh for food. Their passive nature was their undoing, as their numbers have been declining at an alarming rate. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed the basking shark as a Vulnerable Species. In localised areas such as the northeast Atlantic and North Pacific, the species is considered Endangered and Critically Endangered off Canada’s coast The species’ numbers continue to decrease, and if global organizations don’t work harder to prevent overfishing the basking shark may become extinct. Basking sharks are a protected species in many countries. Thanks to international agreements such as the Conventionn on Iinternational Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). It’s also illegal to buy or sell basking shark body parts like fins and cartilage. However, there is still a black market for sharks in many places globally.

Fun Facts About Basking Sharks

- The basking shark has an enormous liver that runs over much of their body length and accounts for up to 25% of their body weight. They use it to help it with buoyancy.

- The basking shark got its name because they swim slowly and methodically near the surface as they feed. They appear to be “basking” in the sun.

- Basking sharks aren’t afraid of boats or people and will swim close to divers.

- This fantastic experience could make the basking shark a valuable commodity for tourism.

- The basking shark has hundreds of small teeth on their upper and lower jaws that they do not need.

- Relative to its size, the basking shark has the smallest brain of all the sharks.

- Basking sharks shed and regrow their gill-rakers, which can take up to five months.

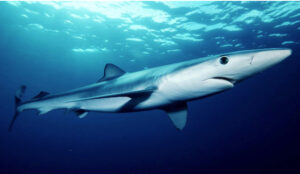

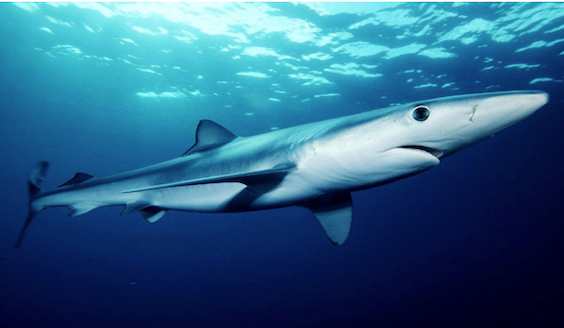

Blue Shark

The blue shark (Prionace glauca), also known as the great blue shark, is a species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae, which inhabits deep waters in the worlds temperate and tropical oceans. Averaging around 3.1 m (10 ft) and preferring cooler waters, the blue shark migrates long distances, such as from New England to South America. It is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

Although generally lethargic, they can move very quickly. Blue sharks are viviparous and are noted for large litters of 25 to over 100 pups. They feed primarily on small fish and squid, although they can take larger prey. Maximum lifespan is still unknown, but it is believed that they can live up to 20 years.

Blue sharks are light bodied with long pectoral fins. Like many other sharks, blue sharks are counter shaded: the top of the body is deep blue, lighter on the sides, and the underside is white. The male blue shark commonly grows to 1.82 to 2.82 m (6.0 to 9.3 ft) at maturity, whereas the larger females commonly grow to 2.2 to 3.3 m (7.2 to 10.8 ft) at maturity. Large specimens can grow to 3.8 m (12 ft) long. Occasionally, an outsized blue shark is reported, with one widely printed claim of a length of 6.1 m (20 ft), but no shark even approaching this size has been scientifically documented. The blue shark is fairly elongated and slender in build and typically weighs from 27 to 55 kg (60 to 121 lb) in males and from 93 to 182 kg (205 to 401 lb) in large females. Occasionally, a female in excess of 3 m (9.8 ft) will weigh over 204 kg (450 lb). The heaviest reported weight for the species was 391 kg(862 lb).

The blue shark is also ectothermic and it has a unique sense of smell. They are viviparous, with a yolk-sac placenta, delivering 4 to 135 pups per litter. The gestation period is between 9 and 12 months. Females mature at five to six years of age and males at four to five. Courtship is believed to involve biting by the male, as mature specimens can be accurately sexed according to the presence or absence of bite scarring. Female blue sharks have adapted to the rigorous mating ritual by developing skin three times as thick as male skin.

The blue shark is an oceanic and epipelagic shark found worldwide in deep temperate and tropical waters from the surface to about 350 m (1,150 ft). In temperate seas it may approach shore, where it can be observed by divers; while in tropical waters, it inhabits greater depths. It lives as far north as Norway and as far south as Chile. Blue sharks are found off the coasts of every continent, except Antarctica. Its greatest Pacific concentrations occur between 20° and 50° North, but with strong seasonal fluctuations. In the tropics, it spreads evenly between 20° N and 20° S. It prefers water temperatures between 12 and 20 °C (54–68 °F), but can be seen in water ranging from 7 to 25 °C (45–77 °F). Records from the Atlantic show a regular clockwise migration within the prevailing currents.

Large numbers of Blue Sharks are tagged and released on the Isles of Scilly each year with many hundreds having been tagged over the years with recoveries off Portugal and the Azores. Squid are the most important prey for blue sharks, but their diet includes other invertebrates, such as cuttlefish, blanket octopuses, and pelagic octopuses, as well as lobster, shrimp, crab, a large number of bony fishes (such as long-snouted lancetfish, snake mackerel and oil fish), small sharks, mammalian carrion and occasional sea birds (such as great shearwaters). Whale and porpoise blubber and meat have been retrieved from the stomachs of captured specimens and they are known to take cod from trawl nets. Sharks have been observed and documented working together as a “pack” to herd prey into a concentrated group from which they can easily feed. Blue sharks may eat tuna, which have been observed taking advantage of the herding behaviour to opportunistically feed on escaping prey. The observed herding behaviour was undisturbed by different species of shark in the vicinity that normally would pursue the common prey. The blue shark can swim at fast speeds, allowing it to catch up with prey easily. Its triangular teeth allow it to easily catch hold of slippery prey. Blue shark meat is edible, but not widely sought after; it is consumed fresh, dried, smoked and salted and diverted for fishmeal. There is a report of high concentration of heavy metals (mercury and lead) in the edible flesh. The skin is used for leather, the fins for shark-fin soup and the liver for oil. Blue sharks are occasionally sought as game fish for their beauty and speed.

Blue sharks rarely bite humans. From 1580 up until 2013, the blue shark was implicated in only 13 biting incidents, four of which ended fatally.

Threasher Shark

Although occasionally sighted in shallow, inshore waters, thresher sharks are primarily pelagic; they prefer the open ocean, characteristically preferring water 500 metres (1,600 ft) and less. Common threshers tend to be more prevalent in coastal waters over continental shelves. Common thresher sharks are found along the continental shelves of North America and Asia of the North Pacific but are rare in the Central and Western Pacific. In the warmer waters of the Central and Western Pacific, bigeye and pelagic thresher sharks are more common. A thresher shark was seen on the live video feed from one of the ROVs monitoring BP’s Macondo oil well blowout in the Gulf of Mexico. This is significantly deeper than the 500 m (1,600 ft) previously thought to be their limit. A bigeye has also been found in the western Mediterranean, and so distribution may be wider than previously believed, or environmental factors may be forcing sharks to search for new territories.

Anatomy and Appearance – Named for their exceptionally long, thresher-like heterocercal tail or caudal fins (which can be as long as the total body length), thresher sharks are active predators; the tail is used as a weapon to stun prey. The thresher shark has a short head and a cone-shaped nose. The mouth is generally small, and the teeth range in size from small to large. By far the largest of the three species is the common thresher, Alopias vulpinus, which may reach a length of 6.1 metres (20 ft) and a mass of over 500 kilograms (1,100 lb). The bigeye thresher, A. superciliosus, is next in size, reaching a length of 4.9 m (16 ft); at just 3 m (10 ft), the pelagic thresher, A. pelagicus, is the smallest.

Thresher sharks are fairly slender, with small dorsal fins and large, recurved pectoral fins. With the exception of the bigeye thresher, these sharks have relatively small eyes positioned to the forward of the head. Coloration ranges from brownish, bluish or purplish gray dorsally with lighter shades ventrally The. three species can be roughly distinguished by the primary colour of the dorsal surface of the body. Common threshers are dark green, bigeye threshers are brown and pelagic threshers are generally blue. Lighting conditions and water clarity can affect how anyone shark appears to an observer, but the colour test is generally supported when other features are examined.

Diet – The thresher shark mainly feeds on pelagic schooling fish such as bluefish, juvenile tuna, and mackerel, which they are known to follow into shallow waters, as well as squid and cuttlefish. Crustaceans and occasionally seabirds are also taken. The thresher shark stuns its prey by using its elongated tail as a weapon.

Behaviour – Thresher sharks are solitary creatures that keep to themselves. It is known that thresher populations of the Indian Ocean are separated by depth and space according to sex. Some species however do occasionally hunt in a group of two or three contrary to their solitary nature. All species are noted for their highly migratory or oceanodromous habits. When hunting schooling fish, thresher sharks are known to “whip” the water. The elongated tail is used to swat smaller fish, stunning them before feeding. Sometimes the thresher shark will slice the fish in half before eating. Thresher sharks are one of the few shark species known to jump fully out of the water, using their elongated tail to propel them out of the water, making turns like dolphins; this behaviour is called breaching. No distinct breeding season is observed by thresher sharks. Fertilization and embryonic development occur internally; this ovoviviparous or live-bearing mode of reproduction results in a small litter (usually two to four) of large well-developed pups, up to 150 cm (59 in) at birth in thin tail threshers. The young fish exhaust their yolk sacs while still inside the mother, at which time they begin feasting on the mother’s unfertilized eggs; this is known as oophagy. Thresher sharks are slow to mature; males reach sexual maturity between seven and 13 years of age and females between eight and 14 years in bigeye threshers. They may live for 20 years or more.

In October 2013, the first picture of a thresher shark giving birth was taken off the coast of the Philippines.

Status – Because of their low fecundity, thresher sharks are highly vulnerable to overfishing. All three thresher shark species have been listed as vulnerable to extinction by the World Conservation Union since 2007 (IUCN).

Portbeagle Shark

The porbeagle (Lamna nasus) is a species of mackerel shark in the family Lamnidae, distributed widely in the cold and temperate marine waters of the North Atlantic and Southern Hemisphere. In the North Pacific, its ecological equivalent is the closely related salmon shark (L. ditropis). It typically reaches 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in length and a weight of 135 kg (298 lb); North Atlantic sharks grow larger than Southern Hemisphere sharks and differ in coloration and aspects of life history. Gray above and white below, the porbeagle has a very stout midsection that tapers towards the long, pointed snout and the narrow base of the tail. It has large pectoral and first dorsal fins, tiny pelvic, second dorsal, and anal fins, and a crescent-shaped caudal fin. The most distinctive features of this species are its three-cusped teeth, the white blotch at the aft base of its first dorsal fin, and the two pairs of lateral keels on its tail.

The porbeagle is an opportunistic hunter that preys mainly on bony fishes and cephalopods throughout the water column, including the bottom. Most commonly found over food-rich banks on the outer continental shelf, it makes occasional forays both close to shore and into the open ocean to a depth of 1,360 m (4,460 ft). It also conducts long-distance seasonal migrations, generally shifting between shallower and deeper water. The porbeagle is fast and highly active, with physiological adaptations that enable it to maintain a higher body temperature than the surrounding water. It can be solitary or gregarious and has been known to perform seemingly playful behaviour. This shark is a placental with oophagy, developing embryos being retained within the mother’s uterus and subsisting on non-viable eggs. Females typically bear four pups every year.

Only a few shark attacks of uncertain provenance have been attributed to the porbeagle. It is well regarded as a game fish by recreational anglers. The meat and fins of the porbeagle are highly valued, which has led to a long history of intense human exploitation. However, this species cannot sustain heavy fishing pressure due to its low reproductive capacity. Direct commercial fishing for the porbeagle, principally by Norwegian long liners, led to stock collapses in the eastern North Atlantic in the 1950s, and the western North Atlantic in the 1960s. The porbeagle continues to be caught throughout its range, both intentionally and as bycatch, with varying degrees of monitoring and management. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the porbeagle as vulnerable worldwide, and as either endangered or critically endangered in different parts of its northern range. Seasonal migrations have been observed in porbeagles from both hemispheres. In the western North Atlantic, much of the population spends the spring in the deep waters of the Nova Scotia continental shelf, and migrates north a distance of 500–1,000 km (310–620 mi) to spend late summer and fall in the shallow waters of the Newfoundland Grand Banks and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In December, large, mature females migrate south over 2,000 km (1,200 mi) into the Sargasso Sea for pupping, keeping deeper than 600 m (2,000 ft) during the day and 200 m (660 ft) at night so as to stay in the cooler waters beneath the Gulf Stream. In the eastern North Atlantic, porbeagles are believed to spend spring and summer in shallow continental shelf waters and disperse northwards to overwinter in deeper waters offshore. Migrating sharks may travel upwards of 2,300 km (1,400 mi), though once they reach their destination they tend to remain within a relatively localized area. In the South Pacific, the population shifts north past 30°S latitude into subtropical waters in winter and spring, and retreats south past 35°S latitude in summer, when sharks are frequently sighted off subantarctic islands.

The porbeagle is an active predator that predominantly ingests small to medium-sized bony fishes. It chases down pelagic fishes such as lancet fish, mackerel, pilchards, herring, and sauries, and forages near the bottom for ground fishes such as cusk, haddock, redfish (i.e., Sebastes, Lutjanus, Trachichthyidae, and Berycidae), cod, hake, icefish, dories, sand lances, lumpsuckers, and flatfish. Cephalopods, particularly squid, also form an important component of its diet, while smaller sharks such as spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) and tope sharks (Galeorhinus galeus) are rarely taken. Examinations of porbeagle stomach contents have also found small shelled molluscs, crustaceans, echinoderms, and other invertebrates, which were likely ingested incidentally, as well as inedible debris such as small stones, feathers, and garbage fragments.

In the western North Atlantic, porbeagles feed mainly on pelagic fishes and squid in spring, and on ground fishes in the fall; this pattern corresponds to the spring-fall migration of these sharks from deeper to shallower waters, and the most available prey types in those respective habitats. Therefore, the porbeagle seems to be an opportunistic predator without strong diet specificity. During spring and summer in the Celtic Sea and on the outer Nova Scotian Shelf, porbeagles congregate at tidally induced thermal fronts to feed on fish that have been drawn by high concentrations of zooplankton.

Porbeagle sharks are tagged and released on the Isles of Scilly where they have an important programme associated with the Wildlife Trust where this year 2022 they caught and tagged and released 18 Porbeagle Sharks.

Hunting New-born porbeagles measure 58–67 cm (23–26 in) long and do not exceed 5 kg (11 lb). Up to a tenth of the weight is made up of the liver, though some yolk also remains in its stomach and continues to sustain the pup until it learns to feed. The overall embryonic growth rate is 7–8 cm (2.8–3.1 in) per month. Sometimes, one pup in a uterus is much smaller than the other, but otherwise normal. These “runts” may result from a dominant, forward-facing embryo eating most of the eggs as they arrive, and/or the mother being unable to provide an adequate egg supply for all her offspring. Birthing occurs from April to September, peaking in April and May (spring-summer) for North Atlantic sharks and June and July (winter) for Southern Hemisphere sharks. In the western North Atlantic, birth occurs well offshore in the Sargasso Sea at depths around 500 m (1,600 ft).

Mako Shark

“Mako” comes from the Māori language, meaning either the shark or a shark tooth. Following the Māori language, “mako” in English is both singular and plural. The word may have originated in a dialectal variation, as it is similar to the common words for shark in a number of Polynesian languages—makō in the Kāi Tahu Māori dialect, mangō in other Māori dialects, “mago” in Samoan, ma’o in Tahitian, and mano in Hawaiian.

The shortfin mako shark is a fairly large species of shark. Growth rates appear to be somewhat accelerated in comparison to other species in the lamnid family. An average adult specimen measures around 2.5 to 3.2m (8.2 50 10.5 ft) in length and weighs from 135-230 kg (298-507 lb). The species is sexually dimorphic, with females typically larger than males. Large specimens are known, with a few large, mature females exceeding a length of 3.8 m (12 ft) and a weight of 550 kg (1,210 lb). The largest taken on hook-and-line was 600 kg (1,300 lb) caught of the coast of California on June 3rd 2013, and the longest verified length was 4.45 m (14.6 ft) caught of the Mediterranean coast of France in September 1973. A specimen caught of the coast of Italy and examined in an Italian fish market in 1881 was reported to weigh an extraordinary 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) at a length of 4 m ((13 ft). Yet another fish was caught off Marmaris, Turkey in the late 1950’s at an estimated size of between 5.7 and 6.19 m (18.7 and 20.3 ft) making it the largest known specimen of the species.

Range and Habitat – The shortfin mako inhabits offshore temperate and tropical seas worldwide. The closely related longfin mako shark is found in the Gulf Stream or warmer offshore waters (e.g. New Zealand and Maine). It is a pelagic species that can be found from the surface to depths of 150 m (490 ft), normally far from land, though occasionally closer to shore, around islands or inlets. One of the very few known endothermic sharks, it is seldom found in waters colder than 16 °C (61 °F).In the western Atlantic, it can be found from Argentina and the Gulf of Mexico to Browns Bank off of Nova Scotia. In Canadian waters, these sharks are neither abundant nor rare. Swordfish are good indicators of shortfin mako populations, as the former are a source of food and prefer similar environmental conditions. Shortfin mako sharks travel long distances to seek prey or mates. In December 1998, a female tagged off California was captured in the central Pacific by a Japanese research vessel, meaning this fish travelled over 2,776 km (1,725 mi). Another specimen swam 2,128 km (1,322 mi) in 37 days, averaging 58 kl (36 miles a day)

The shortfin mako shark feeds mainly upon cephalopods and bony fish including mackerels, tunas, bonitos, and swordfish, but it may also eat other sharks, porpoises, sea turtles, and seabirds. They hunt by lunging vertically up and tearing off chunks of their preys’ flanks and fins. Mako swim below their prey, so they can see what is above and have a high probability of reaching prey before it notices them. In Ganzirri and Isola Lipari, Sicily, shortfin mako have been found with amputated swordfish bills impaled into their head and gills, suggesting swordfish seriously injure and likely kill them. In addition, this location, and the late spring and early summer timing, corresponding to the swordfish’s spawning cycle, suggests they hunt while the swordfish are most vulnerable, typical of many predators.

Shortfin mako sharks consume 3% of their weight each day and take about 1.5–2.0 days to digest an average-sized meal. By comparison, the sandbar shark, an inactive species, consumes 0.6% of its weight a day and takes 3 to 4 days to digest it. An analysis of the stomach contents of 399 male and female mako sharks ranging from 67–328 cm (26–129 in) suggest mako from Cape Hatteras to the Grand Banks prefer bluefish, constituting 77.5% of their diet by volume. The average capacity of the stomach was 10% of the total weight. Shortfin mako sharks consumed 4.3% to 14.5% of the available bluefish between Cape Hatteras and Georges Bank.

The strongest bite recorded during the experiment was roughly 3,000 lbs. of force, or roughly 13,000 newtons. The shortfin mako shark is a yolk-sac ovoviviparous shark giving birth to live young. Developing embryos feed on unfertilized eggs (oophagy) within the uterus during the 15- to 18-month gestation period. They do not engage in sibling cannibalism unlike the sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus). The four to 18 surviving young are born live in the late winter and early spring at a length of about 70 cm (28 in). Females may rest for 18 months after birth before mating again. Shortfin mako sharks bear young on average every three years. A common mating strategy of shortfin mako sharks has been documented as using multiple paternity as a mating strategy, known as polyandry. Polyandry is where the female’s mate with more than one male. This strategy is used to have a single brood sired by multiple males (multiple paternity) and is a common strategy in diverse taxa, including invertebrates and vertebrates.

Lifespan

- Maximum age of 29 years in males (260 cm or 8.5 ft fork length (FL))

- Maximum age of 32 years in females (335 cm or 10.99 ft FL)

- 50% sexual maturity at 8 years in males (185 cm or 6.07 ft FL)

- 50% sexual maturity at 18 years in females (275 cm or 9.02 ft FL)

Attacks on humans

ISAF statistics records 9 shortfin attacks on humans between 1580 and 2022, three of which were fatal, along with 20 boat attacks. This mako is regularly blamed for attacks on humans and, due to its speed, power, and size, it is certainly capable of injuring and killing people. However, this species will not generally attack humans and does not seem to treat them as prey. Most modern attacks involving shortfin mako sharks are considered to have been provoked due to harassment or the shark being caught on a fishing line. Sharks can be attracted to spear fishermen carrying a stuck fish, and may slap them with cavitation bubbles from a swift tail flick. Divers who have encountered shortfin mako note, prior to an attack, they swim in a figure-eight pattern and approach with mouths open.

Conservation. The shortfin mako is currently classified as Endangered by the IUCN, having been up listed from Vulnerable in 2019 and Near-Threatened in 2007. The species is included on Appendix II of CITES which regulates international trade. The species is being targeted by both sport and commercial fisheries, and there is a substantial proportion of bycatch in driftnet fisheries for other species.

Hammer Head Shark

The known species range from 0.9 to 6.0 m (2 ft 11 in to 19 ft 8 in) in length and weigh from 3 to 580 kg (6.6 to 1,300 lb). One specimen caught off the Florida coast in 1906 weighed over 680 kg (1,500 lb). They are usually light grey and have a greenish tint. Their bellies are white, which allows them to blend into the background when viewed from below and sneak up to their prey. Their heads have lateral projections that give them a hammer-like shape. While overall similar, this shape differs somewhat between species; examples are: a distinct T-shape in the great hammerhead, a rounded head with a central notch in the scalloped hammerhead, and an unnotched rounded head in the smooth Hammerhead.

Hammerheads have disproportionately small mouths compared to other shark species. They are known to form schools during the day, sometimes in groups over 100. In the evening, like other sharks,t hey become solitary hunters. National Geographic explains that hammerheads can be found in warm, tropical waters, but during the summer, they participate in mass migration to search for cooler waters. Cephalofoil – The hammer-like shape of the head may have evolved at least in part to enhance the animal’s vision. The positioning of the eyes, mounted on the sides of the shark’s distinctive hammer head, allows 360° of vision in the vertical plane, meaning the animals can see above and below them at all times. They also have an increased binocular vision and depth of visual field as a result of the cephalofoil. The shape of the head was previously thought to help the shark find food, aiding in close-quarters manoeuvrability, and allowing sharp turning movement without losing stability. The unusual structure of its vertebrae, though, has been found to be instrumental in making the turns correctly, more often than the shape of its head, though it would also shift and provide lift. From what is known about the winghead shark, the shape of the hammerhead apparently has to do with an evolved sensory function. Like all sharks, hammerheads have electroreceptory sensory pores called ampullae of Lorenzini. The pores on the shark’s head lead to sensory tubes, which detect electric fields generated by other living creatures. By distributing the receptors over a wider area, like a larger radio antenna, hammerheads can sweep for prey more effectively.

Reproduction – Reproduction occurs only once a year for hammerhead sharks, and usually occurs with the male shark biting the female shark violently until she agrees to mate with him. The hammerhead sharks exhibit a viviparous mode of reproduction with females giving birth to live young. Like other sharks, fertilization is internal, with the male transferring sperm to the female through one of two intromittent organs called claspers. The developing embryos are at first sustained by a yolk sac. When the supply of yolk is exhausted, the depleted yolk sac transforms into a structure analogous to a mammalian placenta (called a “yolk sac placenta” or “pseudo placenta”), through which the mother delivers sustenance until birth. Once the baby sharks are born, they are not taken care of by the parents in any way. Usually, a litter consists of 12 to 15 pups, except for the great hammerhead, which gives birth to litters of 20 to 40 pups. These baby sharks huddle together and swim toward warmer water until they are old enough and large enough to survive on their own. In 2007, the bonnethead shark was found to be capable of asexual reproduction via automictic parthenogenesis, in which a female’s ovum fuses with a polar body to form a zygote without the need for a male. This was the first shark known to do this.

Diet – Hammerhead sharks eat a large range of prey such as fish (including other sharks), squid, octopus, and crustaceans. Stingrays are a particular favourite. These sharks are often found swimming along the bottom of the ocean, stalking their prey. Their unique heads are used as a weapon when hunting down prey. The hammerhead shark uses its head to pin down stingrays and eats the ray when the ray is weak and in shock. The great hammerhead, tending to be larger and more aggressive than most hammerheads, occasionally engages in cannibalism, eating other hammerhead sharks, including its own young. In addition to the typical animal prey, bonnetheads have been found to feed on seagrass, which sometimes makes up as much as half their stomach contents. They may swallow it unintentionally, but they are able to partially digest it. This is the only known case of a potentially omnivorous species of shark.

Relationship with humans – According to the International Shark Attack File, humans have been subjects of 17 documented, unprovoked attacks by hammerhead sharks within the genus Sphyrna since AD 1580. No human fatalities have been recorded

The great and the scalloped hammerheads are listed on the World Conservation Union’s (IUCN) 2008 Red List as endangered, whereas the small lye hammerhead is listed as vulnerable. The status given to these sharks is as a result of overfishing and demand for their fins, an expensive delicacy. Among others, scientists expressed their concern about the plight of the scalloped hammerhead at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Boston. The young swim mostly in shallow waters along shores all over the world to avoid predators.

Shark fins are prized as a delicacy in certain countries in Asia (such as China), and overfishing is putting many hammerhead sharks at risk of extinction. Fishermen who harvest the animals typically cut off the fins and toss the remainder of the fish, which is often still alive, back into the sea. This practice, known as finning, is lethal to the shark.

In native Hawaiian culture, sharks are considered to be gods of the sea, protectors of humans, and cleaners of excessive ocean life. Some of these sharks are believed to be family members who died and have been reincarnated into shark form, but others are considered man-eaters, also known as niuhi. These sharks include great white sharks, tiger sharks, and bull sharks. The hammerhead shark, also known as mano kihikihi, is not considered a man-eater or niuhi; it is considered to be one of the most respected sharks of the ocean, an aumakua. Many Hawaiian families believe that they have an aumakua watching over them and protecting them from the niuhi. The hammerhead shark is thought to be the birth animal of some children. Hawaiian children who are born with the hammerhead shark as an animal sign are believed to be warriors and are meant to sail the oceans. Hammerhead sharks rarely pass through the waters of Maui, but many Maui natives believe that their swimming by is a sign that the gods are watching over the families, and the oceans are clean and balanced.

Shark fin traders say that hammerheads have some of the best quality fin needles which makes them good to eat when prepared properly. Hong Kong is the world’s largest fin trade market and accounts for about 1.5% of the total annual number of fins traded. It is estimated that around 375,000 great hammerhead sharks alone are traded per year which is equivalent to 21,000 metric tons of biomass. However, it is important to note that most sharks that are caught are only used for their fins and then discarded.

Tope

The School shark is a small, shallow-bodied shark with an elongated snout. The large mouth is crescent shaped and the teeth are of similar size and shape in both jaws. They are triangular-shaped, small, and flat school sharks and are dark bluish grey on their upper (dorsal) surfaces and white on their bellies (ventral surface). Juveniles have black markings on their fins. Mature sharks range from 135 to 175 cm (53 50 69 in) for males and 150 to 195 cm (59 to 77 in) for females.

Distribution – The school shark has a widespread distribution and is found mainly near the seabed around coasts in temperate waters, down to depths around 800 m (2,600 ft). It occurs in the Northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea, where it is uncommon and the Southwest Atlantic where it occurs between Patagonia and southern Brazil. It also occurs around the coast of Namibia and South Africa. It is present in the Northeast Pacific where it occurs between British Columbia and Baja California, and in the Southeast Pacific off Chile and Peru. It also occurs round the southern coasts of Australia, including Tasmania, and New Zealand.

The school shark is a migratory species. Animals tagged in the United Kingdom have been recovered in the Azores, the Canary Islands, and Iceland. Tagged individuals in Australia have travelled distances of 1,200 km (750 mi) along the coast and others have turned up in New Zealand.

The school shark feeds primarily on fish. Examination of stomach contents of fish caught off California showed that they were not fussy eaters and consumed whatever fish were plentiful at the time. Their diet was predominantly sardines, midshipmen, flatfish, rockfish, and squid. Feeding is done both in open water and near the seabed as sardines and squid are pelagic animals, while the remainder are benthic species.

The school shark is ovoviviparous; its eggs are fertilised internally and remain in the uterus where the developing foetus feeds on the large yolk sac. Males become mature at a length around 135 cm (53 in) and females around 150 cm (59 in). The gestation period is about one year and the number of developing pups carried varies with the size of the mother, averaging between about 28 and 38. Pups in the same litter may have different sires, possibly because females are able to store sperm for a long time after mating.

The females have traditional “pupping” areas in sheltered bays and estuaries where the young are born. The juvenile fish remain in these nursery areas when the adults move off to deeper waters. The meat of the school shark is consumed in Andalusian cuisine, where it is usually known as cazón. Among recipes are the traditional cazón en adobo in the mainland, and tollos in the Canary Islands. In Mexican cuisine, the term cazón refers to other species, and is prepared similarly. In the United Kingdom, the flesh is sometimes used in “fish and chips” as a substitute for the more usual cod or haddock. In Greek cuisine, it is known as galéos (γαλέος) and usually is served with skordalia (σκορδαλιά), a dip made of mashed potatoes or wet white bread, with mashed garlic and olive oil.

Before 1937, the school shark was caught in California to supply a local market for shark fillet, and the fins were dried and sold in the Far East. Around that date, laboratory tests on its liver showed that it was higher in vitamin A content than any other fish tested. Subsequent to this discovery, it became the subject of a much larger-scale fishery which developed as a result of the high prices obtainable for the fish and its liver.

It became the main source of supply for vitamin A in the United States during World War II, but was overexploited, populations were reduced, and the numbers of fish caught dwindled. Its oil was replaced by a similar product from the spotted spiny dogfish (Squalus suckleyi) and subsequently by lower-potency fish oils from Mexico and South America.

The school shark, along with the gummy shark, is the most important species in the southern Australian commercial fishery. It is fished throughout its range and heavily exploited.

Spur Dogfish

The spurdog is a member of the shark family. It is also referred to as the common spiny dogfish. It can be found living in shoals – that can migrate many miles in one day – all around the coastlines of Britain and Ireland. During the summer months the western and north western regions of Scotland are a prime hotspot for spurdog. They live on and near the seabed, preferring sand or mud, in depths of between 10m and 200m. Amazingly spurdog have been caught in depths of up to 950m. They may swim very close to the surface during night hours.They are a very small and slender shark that will grow to a maximum of around 1m. The snout is quite pointed, they have large black/grey/blue eyes and an underslung mouth. A key means to identify the spurdog is to take a close look at the two dorsal fins – you will find that they have sharp spines on the leading edge. They do not possess an anal fin, and there are white spots on the fish’s back and sides. The colouration of the spurdog tends to be dark grey on the back and either light grey or a brown tinge to the flanks, merging to white underneath.

FEEDING – Spurdogs tend to feed upon bottom-dwelling creatures such as crabs, flatfish, codling and dragnonets, but they will also shoal together and attack schools of smaller fish like herring, sprats and pilchards. To catch a spurdog your best baits will be strips of squid and crab, or a combination of both.

BREEDING – Like most sharks, spurdogs give birth to live young with will have gestated within the mother for a very long time – up to 22 months. Finally the mother will give birth to between three and 11 young. The freshly borne spurdog will be between 18 and 22cm long. Spurdogfish have caught in vast numbers here in West Cornwall with thousands of tons landed at Newlyn and other fishing ports back in the 1980’s. Fortunately the fishing for Spur Dogfish has now ceased

Lesser Spotted Dogfish

Lesser Spotted Dogfish (caniculaare) are small, shallow-water sharks with a slender body and a blunt head. The two dorsal fins are located towards the tail end of the body. The texture of their skin is rough, similar to the coarseness of sandpaper. The nostrils are located on the underside of the snout and are connected to the mouth by a curved groove. The upper side of the body is greyish brown with dark brown spots. They deposit egg cases protected by a horny capsule with long tendrils. Egg cases are mostly deposited on macroalgae in shallow coastal waters. When the egg cases are deposited farther from shore, they are placed on sessile erect invertebrates. Egg cases usually measure 4 cm by 2 cm, without ever exceeding 6 cm. These egg cases can be found around the coasts of Europe. The embryos develop for 5–11 months depending on the sea temperature, and the young are born with a measurement of 9–10 cm. Spawning can take place almost year round. However, there can be seasonal patterns in spawning activity as well. For example, S. canicula females located off the Mediterranean coast of France lay their eggs from March to June and in December. In the waters surrounding Great Britain, egg laying occurs in spring with a gap between August and October. On the Tunisian coast, the sharks lay their eggs starting in spring, peaking in the summer and then slightly decreasing during autumn. Males reach sexual maturity with a length of about 37.1–48.8 cm. Females reach sexual maturity with a length of 36.4–46.7 cm.

Lesser Spotted Dogfishare an opportunistic species, preying on a wide variety of organisms. Decapod crustaceans, molluscs and fishes are their main prey, but echinoderms, polychaetes, sipunculids and tunicates may also be eaten. Dietary preferences change with age; younger animals prefer small crustaceans, while older animals prefer hermit crabs and molluscs. Feeding intensity is highest during the summer due to the higher availability of prey life. Diet composition varies with body size. There are no significant differences in feeding habits between male and female S. canicula. Juveniles of S. canicula feed by anchoring the prey item on the dermal denticles near their tail, and tearing bite-sized pieces off with rapid head and jaw movements, a behaviour known as “scale rasping”. Use of dermal denticles to assist in feeding was first documented in this species.

Caniculais one of the most abundant elasmobranchs in the northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean. It is regularly caught by near-shore fisheries, but the majority taken by commercial fishermen and recreational anglers are discarded. Studies have shown that post-discard survival rates are extremely high, around 98%. Although localized depletion may have occurred in some areas, surveys have shown that populations are stable or are even increasing throughout the majority of its range. However, continued monitoring of landing and discarded data is important to avoid any future decline. This species is currently listed as being of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, because there is no evidence to indicate that the global population has declined significantly.

S. canicula is currently of low commercial value. In the recent past it was one of the species sold in English and Scottish fish and chip shops as rock salmon, rock eel, huss or Sweet William. In other parts of its range it is occasionally baked or used in fish soup. Its hard skin has been used as a substitute for pumice, but the fact that catsharks have to be skinned before they can be filleted discourages commercial fishermen from catching this species.

Greater spotted Dogfish

The nurse hound (Scyliorhinus stellaris), also known as the large-spotted dogfish, greater spotted dogfish or bull huss, is a species of catshark, belonging to the family Scyliorhinidae, found in the north eastern Atlantic Ocean. It is generally found among rocks or algae at a depth of 20–60 m (66–197 ft). Growing up to 1.6 m (5.2 ft) long, the nurse hound has a robust body with a broad, rounded head and two dorsal fins placed far back. It shares its range with the more common and closely related small-spotted catshark (S. canicula), which it resembles in appearance but can be distinguished from, in having larger spots and nasal skin flaps that do not extend to the mouth.

Nurse hounds have nocturnal habits and generally hide inside small holes during the day, often associating with other members of its species. A benthic predator, it feeds on a range of bony fishes, smaller sharks, crustaceans, and cephalopods. Like other catsharks, the nurse hound is oviparous in reproduction. Females deposit large, thick-walled egg cases, two at a time, from March to October, securing them to bunches of seaweed. The eggs take 7–12 months to hatch. Nurse hounds are marketed as food in several European countries under various names, including “flake”, “catfish”, “rock eel”, and “rock salmon”. It was once also valued for its rough skin (called “rub skin”), which was used as an abrasive. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the nurse hound as Vulnerable, as its population in the Mediterranean Sea seems to have declined substantially from overfishing

The nurse hound is found in the north-eastern Atlantic from southern Norway and Sweden to Senegal, including off the British Isles, throughout the Mediterranean Sea, and the Canary Islands. It may occur as far south as the mouth of the Congo River, though these West African records may represent misidentifications of the West African catshark (S. cervigoni). Its range seems to be rather patchy, particularly around offshore islands, where there are small local populations with limited exchange between them. The nurse hound can be found from the intertidal zone to a depth of 400 m (1,300 ft), though it is most common between 20 m (66 ft) and 60–125 m (197–410 ft). This bottom-dwelling species prefers quiet water over rough or rocky terrain, including sites with algal cover. In the Mediterranean, it favours algae-covered coral.

The nurse hound attains a length of 1.6 m (5.2 ft), though most measure less than 1.3 m (4.3 ft). This shark has a broad, rounded head and a stout body that tapers towards the tail. The eyes are oval in shape, with a thick fold of skin on the lower rim but no nictitating membrane. Unlike in the small-spotted catshark, the large flaps of skin beside the nares do not reach the mouth. In the upper jaw, there are 22–27 tooth rows on either side and 0–2 teeth at the symphysis (centre); in the lower jaw, there are 18–21 tooth rows on either side and 2–4 teeth at the symphysis.

Primarily nocturnal, nurse hounds spend the day inside small holes in rocks and swim into deeper water at night to hunt. Sometimes two sharks will squeeze into the same hole, and several individuals will seek out refuges within the same local area. In one tracking study, a single immature nurse hound was observed to use five different refuges in succession over a period of 168 days, consistently returning to each one over a number of days before moving on. Nurse hounds may occupy refuges to hide from predators, avoid harassment by mature conspecifics, and/or to facilitate thermoregulation. In captivity, these sharks are gregarious and tend to rest in groups, though the individuals comprising any particular group changes frequently. This species is less common than the small-spotted catshark.

The nurse hound feeds on a variety of benthic organisms, including bony fishes such as mackerel, deep-water, dragonets, gurnards, flatfishes, and herring, and smaller sharks such as the small-spotted catshark. It also consumes crustaceans, in particular crabs but also hermit crabs and large shrimp, and cephalopods. Given the opportunity, this shark will scavenge. Adults consume relatively more bony fish and cephalopods, and fewer crustaceans, than juveniles. Known parasites of this species include the monogeneans Hexabothrium appendiculatum and Leptocotylemajor, the tapeworm Acantho bothrium coronatum, the trypanosome Trypanosoma scyllii, the isopod Ceratothoa oxyrrhynchaena, and the copepod Lernaeopoda galei. The netted dog whelk (Nassarius reticulatus) preys on the nurse hound’s eggs by piercing the case and extracting the yolk. Like other members of its family, the nurse hound is oviparous. Known breeding grounds include the River Fal estuary and Wembury Bay in England, and a number of coastal sites around the Italian Peninsula, in particular the Santa Croce Bank in the Gulf of Naples. Adults move into shallow water in the spring or early summer, and mate only at night. The eggs are deposited in the shallows from March to October. Although a single female produces 77–109 oocytes per year, not all of these are ovulated and estimates of the actual number of eggs laid range from 9 to 41. The eggs mature and are released two at a time, one from each oviduct. Each egg is enclosed in a thick, dark brown case measuring 10–13 cm (3.9–5.1 in) long and 3.5 cm (1.4 in) wide. There are tendrils at the four corners, that allow the female to secure the egg cases to bunches of seaweed (usually Cystoseira spp. or Laminaria saccharina).

Eggs in the North Sea and the Atlantic take 10–12 months to hatch, while those from the southern Mediterranean take 7 months to hatch. The length at hatching is 16 cm (6.3 in) off Britain, and 10–12 cm (3.9–4.7 in) off France. Newly hatched sharks grow at a rate of 0.45–0.56 mm (0.018–0.022 in) per day, and have prominent saddle markings. Sexual maturity is attained at a length of 77–79 cm (30–31 in), which corresponds to an age of four years if hatchling growth rates remain constant. This species has a lifespan of at least 19 years. The impact of fishing activities on the nurse hound is difficult to assess as species-specific data is generally lacking. This species is more susceptible to overfishing than the small-spotted catshark because of its larger size and fragmented distribution, which limits the recovery potential of depleted local stocks. There is evidence that its numbers have declined significantly in the Gulf of Lion, off Albania, and around the Balearic Islands. In the upper Tyrrhenian Sea, its numbers have fallen by over 99% since the 1970s. These declines have led the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to list the nurse hound as Vulnerable.